Similarly to branding ‘endurance exercise’ as all the same thing, strength training is often considered to be a ‘package deal’.

The problem with bundling everything under one big umbrella is that training methods and the adaptations of long duration, HIIT, pacing, and other types of endurance training are different. All of these methods are important and affect your overall fitness and performance in unique ways.

Strength training is no different. If you change the order or type of exercise, the number of exercises, sets and repetitions, inter-set rest duration, or load relative to maximum, the training stimulus can change dramatically.

Here I shed light on how varied strength training actually is (or can and should be), why endurance athletes should work on their strength, and reveal the most promising use of heart rate monitoring in strength training.

Different types of strength training for endurance athletes

As already mentioned, strength training isn’t all the same: there are several different types of strength you can and should work on. As each /strength) training method targets specific neuromuscular characteristics, you should plan your workouts based on your individual goals.

Maximum strength

Training with very high loads (e.g. >90% of maximum) for 1-4 repetitions per set and allowing 2-5min rest between sets will develop the ability to activate and coordinate muscular contraction to allow us to lift heavy loads, i.e. develop maximum strength.

Using this type of strength training will limit the amount of muscle growth, and has been classified as ‘neural strength training’.

Explosive strength

To develop the ability to activate the muscles rapidly, each repetition should be performed as fast as possible.

People typically use light to moderate loads during explosive strength training, particularly if the sport requires a lower force level, such as running or long-distance cycling.

Increasing muscle mass

A ‘bodybuilding’ workout using moderate loads (50-85% of maximum) for 8-12 repetitions per set and 1-2min rest between sets will stimulate increases in both strength and muscle mass.

Muscular endurance

Lighter loads (20-50% of maximum) for 15-30 repetitions per set with 30-90 seconds rest (or even no rest if doing circuit training or supersets) will stimulate ‘muscular endurance’ adaptations.

If you use light loads to extreme repetition ranges (e.g. 50-100 per set) then muscle growth is similar compared to the ‘bodybuilding’ example that was mentioned above.

Strength training for endurance athletes

It seems that scientific research on strength training for endurance athletes and endurance athletes themselves favor maximum strength and explosive strength training workouts.

But, that is not the whole truth.

Each type of strength training can be useful and incorporated into an endurance-focused training program:

- Increase maximum strength to make your sport-specific actions more economical as the absolute force level during endurance exercise is lower relative to your maximum strength.

- Increase muscle mass and the buffering capacity that comes from moderate load training to be able to deal with higher lactate loading.

- Increase muscular endurance to accomplish a higher workload of endurance training or reduce your recovery times between intervals.

- Increase explosive strength to improve the kick at the end of the race.

Even bodybuilding workouts won’t turn you into Arnold.

Don’t be frightened that you’ll suddenly become overly muscular even when using the moderate load ‘bodybuilding’ workout, actual muscle growth is blunted when high amounts of endurance training are performed so even bodybuilding workouts won’t turn you into Arnold.

If you’re a competitive endurance athlete looking to integrate strength training into your training program, try prioritizing strength training blocks, e.g. 8-10 weeks in duration, where 2-3 strength workouts per week are performed concurrently with a small (20-30%) reduction in endurance training volume.

These strength-focused ‘blocks’ can be inserted throughout the year where most appropriate, e.g. post-season or pre-competitive season where high-intensity endurance training is at a minimum, or during periods of injury when you can’t perform your normal endurance training program. As mentioned above, popular training methods among endurance athletes focus on maximum strength and explosive strength.

Strength training for recreational exercisers

For recreational exercisers, it’s relatively simple to integrate strength training e.g. twice per week into your normal training program since your overall training volume is quite low.

It seems that low frequency of endurance plus strength training allows continuous improvements in both elements of fitness. e.g. 2-4 times per week endurance plus 2 times per week strength training.

Here, I’d recommend that you perform a total body workout that targets all major muscle groups, but, of course, you can focus on certain muscle groups within the total body workout for variation and/or continued adaptation.

This practice can continue

throughout the year for recreational exercisers. Within this practice, it would

be beneficial to follow either a linearly periodized program or a non-linear periodized

program to ensure progression.

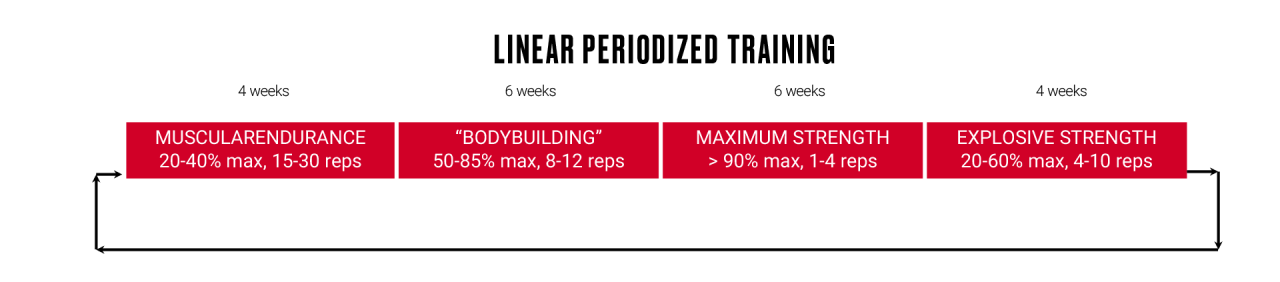

A linear program basically begins with a few weeks of muscle endurance training, followed by a few weeks of a ‘bodybuilding’ workout, followed by a few weeks of maximum strength and finishing with a few weeks of explosive strength training – and then repeat with some slight variations in key training variables from the first cycle.

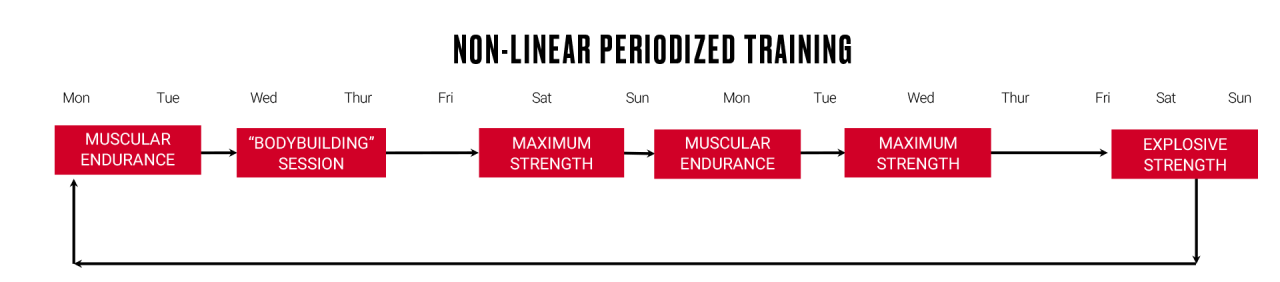

Non-linear periodization is basically mixing up these different workouts so that you do something different each time you visit the gym.

Heart rate monitoring during strength training

Heart rate monitoring has been used extensively to classify training load in endurance training, but scientific interest in this issue for strength training has only begun in earnest since the turn of the century.

A word of caution though, heart rate responds in a different way to strength training than to endurance training. For example, performing both cycling and squat exercise at the lactate threshold will lead to your heart rate remaining approximately 10-20 beats per minute lower during squatting than during cycling.

Therefore, if traditional ‘training zones’ is to be established, then individual heart rate/lactate assessment should be made. This is really difficult to assess since they would need to be tested individually for many different exercises and workouts.

For example, it’s natural that circuit training and other muscular endurance training workouts lead to greater increases in heart rate than maximum strength training where only a few repetitions per set are performed.

Monitoring heart rate to maintain a specific cardiorespiratory load, and help to regulate pacing, could be most useful during circuit training exercise or where multiple exercises are performed in series over several minutes (e.g. WODs for those interested in Cross-FitTM).

Also, different exercises lead to different heart rate responses even when performing the same number of repetitions with the same rest period; arm exercises, especially using two arms versus one arm, lead to greater heart rate responses than leg exercises.

Heart rate as a tool to measure recovery

Perhaps the most promising use of monitoring heart rate for strength training is during recovery after the workout.

There seems to be emerging evidence that following heart rate variability over 24-48 hours after workouts to infer changes in autonomic nervous system function can be a reliable tool for athletes and training enthusiasts.

After each strength training workout, heart rate variability is modified. This is typically observed within 30 minutes after the workout and can persist for up to 48 hours.

It appears that high volume strength training workouts that are more metabolically challenging and induce greater blood lactate responses lead to greater changes in heart rate variability. Therefore, these types of workouts may need longer recovery, and heart rate variability may be a tool to determine when to perform the next workout.

One recent study has actually used post-workout heart rate variability to prescribe the subsequent workout in an attempt to optimize training adaptation. We need further scientific studies to see if this practice is really better for training planning, but it seems plausible at present.

Finally, studies have shown that the post-workout modifications to heart rate variability are reduced after several weeks of training, i.e. as the person adapts to a specific type of strength training workout. This information can help you decide to change the type of strength training you perform to update the training stimulus and achieve continuous improvements.

In conclusion

There is good evidence that endurance athletes benefit from integrating strength training into their training programs.

There is also reason to believe that monitoring recovery of heart rate variability may aid strength training programming, but this requires an understanding of how your body responds and some trial-and-error.

Hopefully, this information gives you a new dimension to your training and something to try in the near future. Happy ‘playing’ and successful workouts

If you liked this post, don’t forget to share so that others can find it, too.

Or give it a thumbs up!

I like this article

Please note that the information provided in the Polar Blog articles cannot replace individual advice from health professionals. Please consult your physician before starting a new fitness program.