‘Is power going to replace heart rate?’ has become a frequently asked question as measuring power is becoming more and more common in sports.

The question about power vs. heart rate is no longer in the minds of cyclists only but increasingly on the lips of many runners, too.

Traditionally, power has been measured in cycling but with the new wrist-based Running Power technology paving the way to the future of running, the question about power vs heart rate is no longer in the minds of cyclists only but increasingly on the lips of many runners, too.

On that note, it’s vital to stress that absolute values of cycling and running powers are not comparable because they each use a different methodology. What combines the two is that they both reflect changes in muscle power.

To shed light on the power vs heart rate discussion, especially in the context of running, let’s take a look at the main differences between power and heart rate and if and when you should favor one over the other.

Power vs heart rate – What are the differences?

First, let’s define what we’re talking about here:

Heart rate is a surrogate measure of the heart’s power, controlled by the involuntary (autonomic) nervous system. It measures the rate at which the heart works so if the heart rate changes, also heart’s work rate changes.

Power is a measure of skeletal muscle power, controlled by the voluntary nervous system. It measures the rate at which skeletal muscles, as opposed to the heart, do mechanical work.

Heart rate reacts with a delay

Being controlled by two different parts of the central nervous system (involuntary and voluntary nervous system) means that it’s possible to suddenly contract a skeletal muscle simply by thinking, but impossible to do the same for the heart.

It’s possible to suddenly contract a skeletal muscle simply by thinking, but impossible to do the same for the heart.

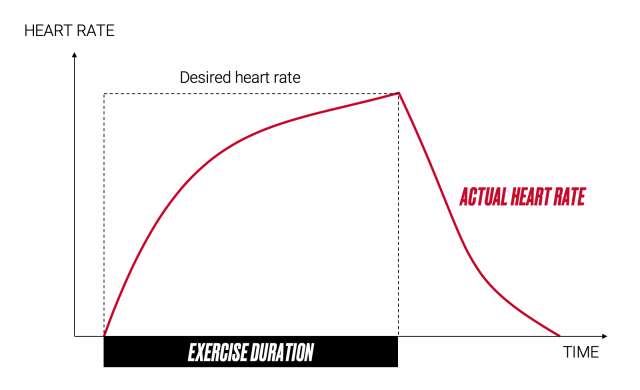

In essence, except for a ‘fight or flight’ reaction – where heart rate may increase substantially in a short period of time – heart rate doesn’t increase until muscles start contracting. In such a case, contracting muscles release carbon dioxide to the bloodstream, which is a signal for the heart rate to rise. In other words, muscle power defines the desired state in which the actual heart rate follows with a delay (Figure 1).

Due to this complex decision-making system, heart rate needs time to achieve the desired state. The lag between the initial state and the desired state can be several minutes depending on the initial heart rate and increase in muscle power.

Figure 1. Comparison of actual and desired heart rate during heavy exercise bout lasting several minutes.

Power shows the full capacity of the muscles

The main purpose of the heart is to supply oxygen to muscles. However, the muscle can work without oxygen too. When muscles work using oxygen, that’s called aerobic metabolism, and when muscles work without oxygen, that’s called anaerobic metabolism.

In practice, this means that:

- For low- to medium-power efforts, such as racing a marathon, we use the aerobic system

- For short, all-out exercise bouts, like 100 m sprints, we use the anaerobic system

- For everything else, we use a combination of these two systems.

Heart rate is suitable for measuring sports performance that requires aerobic power but not the best measure for actions that have a strong anaerobic power component.

Maximal power supplied by the muscles is twice as high as maximal aerobic power.

Quantitatively speaking, maximal power supplied by the muscles is twice as high as maximal aerobic power (Figure 2).

When the anaerobic energy system is used, the muscles take energy from high-energy phosphates. The drawback is that high-energy phosphates are depleted in 10–20 seconds and it takes a while to restore them.

The key point here is this: When we measure muscle power, we can ‘see’ the full power capacity of the muscles that we would otherwise miss.

Figure 2. Comparison of maximal aerobic power and maximal muscle power.

Should you monitor power or heart rate?

So far we have learned that:

1) Heart rate follows changes in muscle power with a delay

2) Heart rate indicates only half of the power that muscles can produce

Next, let’s explore when heart rate should be the preferred measure and when you should opt to measure power.

Choose heart rate

- If you want to compare a variety of different sports. For example, if you want to compare workloads from running and swimming, heart rate is your only choice, because power is currently available for cycling and running only.

Choose power

- If you do a lot of high-power interval training. In this case, you’ll almost certainly use the anaerobic energy system, and heart rate can’t give you realistic feedback on how much your anaerobic energy system was stressed.

That’s it. Those are the only reasons to go for either heart rate or power-based training alone, but there are several reasons to combine the two.

Power and heart rate work best together

First and foremost, because heart rate measures stress to the heart and power measures stress to your skeletal muscles, it’s best to measure both systems if you want to maintain progressive training, but avoid overtraining.

Vary your training

When you measure both heart rate and power, you can add variation to your training by sometimes training with a high muscle load and sometimes with a high cardio load. If you notice that your Muscle Load values are higher than usual and you feel soreness in your muscles, it’s a good idea to go for cardio training.

To help you make progress without overdoing it, the Training Load Pro feature on the Polar Vantage series multisport watches calculates both Cardio load and Muscle load and combines them with your Perceived load.

Adjust training

Power to heart rate ratio is a useful indicator of the body’s response to training. For example, you can follow your training sessions that are performed at comparable power, and if you notice a consistent increase in heart rate as compared to normal, you might be suffering from stress.

You can check this with the Orthostatic Test which is part of the Recovery Pro feature on the Polar Vantage V2 multisport watch. If you seem to be stressed, the Recovery Pro feature will instruct you to reduce your training load accordingly. To achieve this, it’s typically better to lower intensity and maintain volume, rather than the other way around.

Monitor progress

On the other hand, if your heart rate has decreased, while your power has remained the same, you can congratulate yourself. This is often an indication of improved cardiovascular fitness.

If your heart rate has decreased, while your power has remained the same, you can congratulate yourself.

Power to heart rate ratio is an especially powerful tool for trail runners. As trails typically contain a lot of altitude variation, using speed as a measure of effort doesn’t tell you much. It’s better to measure power, which considers variation in altitude.

In conclusion

Lastly, a word of caution: Power (in watts) is affected by your weight (technically speaking, this should read mass) and you should pay special attention when comparing power over a long period of time: If your weight (mass) changes, the power values change accordingly.

In summary, as heart rate measures stress to the heart and power measures stress to skeletal muscles, neither makes the other obsolete – they are, rather, complementary measures. You’ll achieve the best results by combining heart rate with power.

Good luck with your training with heart rate and power!

If you liked this post, don’t forget to share so that others can find it, too.

Please note that the information provided in the Polar Blog articles cannot replace individual advice from health professionals. Please consult your physician before starting a new fitness program.