There are many ways of measuring how hard we’re working when we run. Pace is the most common: to go fast, we need to push harder – that’s easy enough to understand. Pace, however, may not always be the best indicator of your running intensity. Think of running uphill: it takes more effort, but pace is slower.

The good news is there’s a new metric that can help monitor your effort more accurately. That’s running power.

In short, running power measures, in Watts, the effort required for every segment of your run. The higher the Watts, the more power you’re generating with every step. In other words, this metric is used to quantitatively and more objectively measure how much energy runners use during different conditions and time points in their run.

Of course, talking about power isn’t new. Cyclists have been doing it for decades. So considering how crucial power meters can be for cyclists, it’s not surprising that runners are starting to catch on as well.

Using this additional form of data can definitely benefit runners, and it takes some of the remaining guesswork out of your training and racing. If you already know your pace, your heart rate, and your distance covered, bringing power into the equation – literally – can monitor that data even more precisely.

Here’s what runners should know about running power – and why tracking more than distance and heart rate just may change the game (or at least your next big race).

What is running power?

Essentially running power is the measurement, in Watts, of how much work you’re putting in while you run.

We produce power as we run. Most of this power supplied by muscles is converted to heat and the small fraction that doesn’t turn into heat, propels us forward.

That’s called mechanical power, or in this case, running power. Power indicates how much force and speed a runner is exerting at any given moment. In other words, power is just how much you’re doing and how fast you’re doing it.

Running with power

For runners, power is a phenomenal metric to monitor how hard they are working during every segment of a run whether they’re running on the flat or uphill. This way, it complements more common metrics like heart rate and pace because power tracks the actual work output of every step rather than your heart’s response, or the speed (pace) resulting from the work needed to produce the output.

You may think you’re working your butt off, and your heart rate may be skyrocketing, but looking specifically at power numbers can help you understand how hard you’re truly working and how that relates to your fullest potential.

Let’s take a look at a couple of examples. Heat, altitude, or your energy levels are factors that can affect your heart rate and make your heart beat a little bit faster than usual while running. If this happens, you may think you’re working your butt off, and your heart rate may be skyrocketing, but looking specifically at power numbers can tell otherwise: despite your heart beating faster, your power output might be no different than any other day running the same segment at the same pace.

Similarly, when you run uphill, your pace slows down and you need to generate more power to propel you forward – that’s the battle against gravity. In this situation, power rather than pace can tell the actual intensity of your run.

Using power as a measuring factor during your runs can help you make real-time effort-based analyses – measured in watts – that’ll help you reach your peak performance.

SAME PACE, DIFFERENT POWER

Running, unlike cycling, is greatly affected by the biomechanics of the athlete, so insights into the biomechanical economy of the runner can be measured. This way, any technical changes the runner makes can be objectively evaluated for performance.

FOR EXAMPLE:

- Two athletes can run at the same pace, with entirely different power.

- Or two athletes can run at the exact same power, and same body mass, but at entirely different paces.

For a runner to move they must push a force into the ground through their legs and feet, to lift their body up into the air. This airborne lift is required for running, but if a runner goes too far up in the air, it’s not conducive to running forward very fast. Work is still being accomplished, but it’s moving upward, instead of forward.

The movement can also be lateral. A change in technique that a runner makes, can suddenly be more effective at transferring their efforts forward. Foot-strike, upper body position and many other small changes in running technique can take the same power output and make it faster.

How Does running power HELP?

The upside to using power as a training tool is that understanding even more about your body can make you perform better. It can show you how efficient you are during your workouts, which can help you (or your coach) tweak your training, form, and technique accordingly.

You may find that you’re outputting more power at a lower heart rate, which is usually an indicator of increased running efficiency. Thus, in the long run, by tweaking your form you may actually perform more efficiently.

Plus, power takes into consideration not just heart rate and pace, but also your rate of perceived effort. Having more data on hand – like your functional threshold power and your VO2 max – equals smarter training and, in most cases, better results.

RUNNING POWER AND THE BATTLE AGAINST GRAVITY

Running power is a better measure of intensity than pace typically is.

For example, your power can stay the same when going uphill, but clearly if you kept the same power on the uphill as the flat, the uphill portion will be slower. However, you’re working the same effort and intensity, despite the slowing of the pace due to the battle against gravity now being prominent.

The opposite is also true when running downhill – the pace will likely increase greatly but your work rate is lower as gravity is the force placed on the body to pull it down the hill. So, even though pace increases, your effort and intensity decreases. Therefore, pace is not effective for measuring intensity, especially on hilly courses.

Also consider interval workouts, where you do a certain distance or time, either on a course or track. Yes, you might run fast on the interval, but you’re not sustaining that pace the whole time, you’ve added in recovery periods. Pace for the workout will be affected by the recovery periods where you’re standing around, walking or jogging extremely slow. If it’s a course with hills, you’re adding to the variation of pace.

Power is much more effective than pace to account for variations with rest intervals or hills.

RUNNING POWER AND HEART RATE DATA

Combining running power and pace with heart rate data offers unique opportunities for runners.

The advantages this provides is the opportunity to see where a small change in power can lead to a big jump or decline in heart rate. This type of data becomes very helpful in hot conditions, or longer race efforts where pacing is challenging and critical.

As athletes begin to collect more heart rate and power data on themselves, this relationship and the key points of exponential change can likely become more clear, and training and racing strategies can be devised to maximize this.

If you notice a certain heart rate required to hold a common aerobic power value while running, then you’re seeing aerobic economy fitness improvements. This is much more objective than pace/heart rate comparisons, as pace can be affected by hills, or even GPS error.

With power, you can run at a steady workout, even if going uphill, without the slowing of pace affecting the ratio of power/heart rate.

With power, you can run at a steady workout, even if going uphill, without the slowing of pace affecting the ratio of power/heart rate.

Related: Power vs. Heart Rate

LET POWER GUIDE YOUR RUNS

Polar introduced the world’s first wrist-based running power in 2018 with the Polar Vantage V multisport watch. Since then, many of our watches, including Polar Vantage V2, Polar Grit X Pro and Polar Pacer Pro, can measure power directly from the wrist.

You can use this metric to guide your runs by following the different power zones.

Using this feature is simple, not much different than looking at any other running metric. You can set up different training views for running workouts, including power metrics to see your power output, in Watts, at any moment of your run. Your watch will display maximum power, average power, lap power, and more. It can also show your current power zone, so you always run at the right intensity.

Next, let’s see how to set up your running power zones to guide your training sessions.

FIND YOUR MAXIMAL AEROBIC POWER

Just like heart rate training, training with running power is based on power zones that can be determined by using maximal aerobic power (MAP).

If you don’t know your maximal aerobic power, but you know your VO2max, you can update it to Polar Flow under “Physical settings” and we’ll estimate your maximal aerobic power based on your VO2max.

There’s also a test to estimate your maximal aerobic power:

- Because MAP can be sustained on average for 6 minutes, you can estimate it with a 6-minute time-trial run.

- To complete the test, run as fast as you can for six minutes.

- After finishing the test, look at your average power, which equates to your MAP.

- Then update your MAP in your power zone settings.

Once you’re all set, it’s time to look at the different power zones.

SET UP YOUR RUNNING POWER ZONES

There are five power zones to help you achieve your training goals.

ZONE 1: 55%–70% OF MAXIMAL AEROBIC POWER

- This zone is for easy runs or recovery sessions. Running in zone 1 builds up your basic endurance.

ZONE 2: 70%–85% OF MAXIMAL AEROBIC POWER

- This is the marathon running zone. You should be able to maintain this level continuously for up to one hour. Alternatively, you can split your training into e.g. 4 x 1.6 km intervals.

- Zones 1 and 2 are the bread and butter of your training. You should aim to spend most of your training in these zones. If you’re racing and your distance includes running in zone 2, reduce training in this zone during the competitive season.

ZONE 3: 85%–100% OF MAXIMAL AEROBIC POWER

- Improves your maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max). In this zone, you should be able to complete 4–6-minute interval runs.

- Zone 3 is for your training season. Include it in your training program for one month at a time.

ZONE 4: 100%–115% OF MAXIMAL AEROBIC POWER

- Use this zone for long interval runs (150-600 m) that create a burning sensation in your muscles (as an indication of lactate accumulation).

- Zone 4 is for experienced runners who prepare for competition. For the rest of us, it’s okay to be in zone 4, but a burning sensation in your muscles can strip the fun out of running.

ZONE 5: MORE THAN 115% OF MAXIMAL AEROBIC POWER

- Improve your maximal power production in short interval runs (< 150 m).

- Zone 5 is safe for all, but it may be difficult to achieve when running on flat terrain. A good alternative is to do uphill running sessions where reaching zone 5 is easier.

MEASURING RUNNING POWER FROM THE WRIST

With wrist-based running power measurement, you don’t need a separate foot pod or power meter – your sports watch automatically measures power from the wrist during your runs.

Being able to look at your watch and see your running power numbers is particularly useful for interval training and hill running.

Interval training is effective and fun. However, to avoid bad habits, bear in mind the following advice.

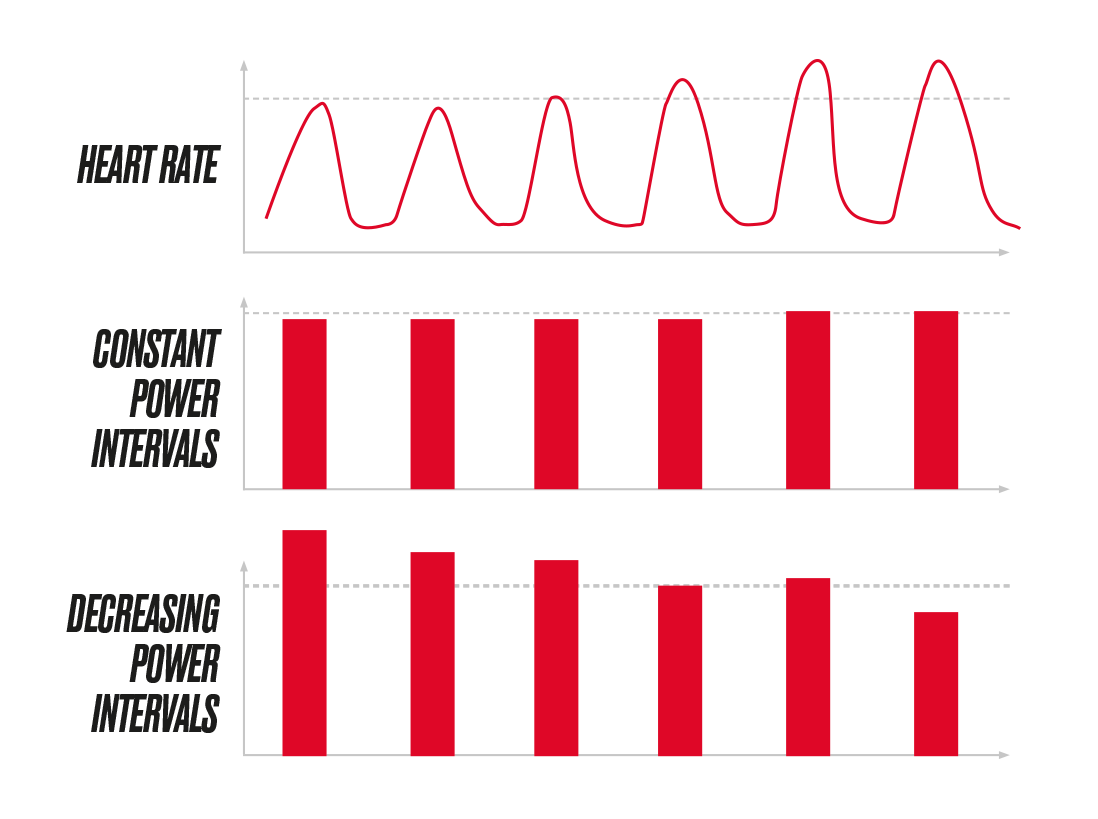

During interval training, you should hold your running power constant between the intervals, or even slightly increase power towards your last run. This way you won’t be at the limits of your strength and will be able to maintain the correct running technique, which will help you avoid running injuries.

Note that your heart rate may increase as you progress towards your last runs (as in the example below). This is normal and depends on the length of each workout and recovery interval.

Example. Heart rate and interval training with constant (good) or decreasing (bad) power.

OBTAIN MAXIMAL POWER: RUN IN HILLY TERRAIN

To obtain maximal power, you need to activate as much muscle mass as you can. This is easier if you run against a positive slope. You can’t attain maximal power when you run on flat terrain, not even at maximal speed.

Running downhill forces your muscles to produce more force than running uphill. Thus, although you produce less power downhill than uphill, downhills put more stress on your muscles.

Although you produce less power downhill than uphill, downhills put more stress on your muscles.

This may lead to muscle pain 24-48 hours after training (known as delayed-onset muscle soreness), but that pain is harmless, and your muscles potentially become more fatigue resistant.

Overall, running in hilly terrain is a good alternative for all runners and poses a different kind of stress to muscles than running on flat ground.

TRY RUNNING POWER Yourself WITH POLAR PACER PRO

Running power has been available in Polar watches for some time. The latest model to include a built-in power meter is Polar Pacer Pro, our latest addition to our family of running watches. Every aspect of Polar Pacer Pro has been engineered for an unrivaled running experience. With the inclusion of running power, Polar Pacer Pro has all the features you need to fine-tune your training and become a better runner.

Want to know more about Polar Pacer Pro? Here’s everything you need to know about the Polar Pacer Series.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to share so that others can find it, too.

Or give it a thumbs up!

I like this article

Please note that the information provided in the Polar Blog articles cannot replace individual advice from health professionals. Please consult your physician before starting a new fitness program.